White Horse: Trip

Lea Martini, Chris Leuenberger, Xavier Fontaine [performance]

Julia Jadkowski, Lea Martini, Chris Leuenberger [concept]

Jan Fedinger, Fabian Lehmann, Attila Nemeth [light], Coordt Linke [sound]

Dampfzentrale Bern (Switzerland), May 2009

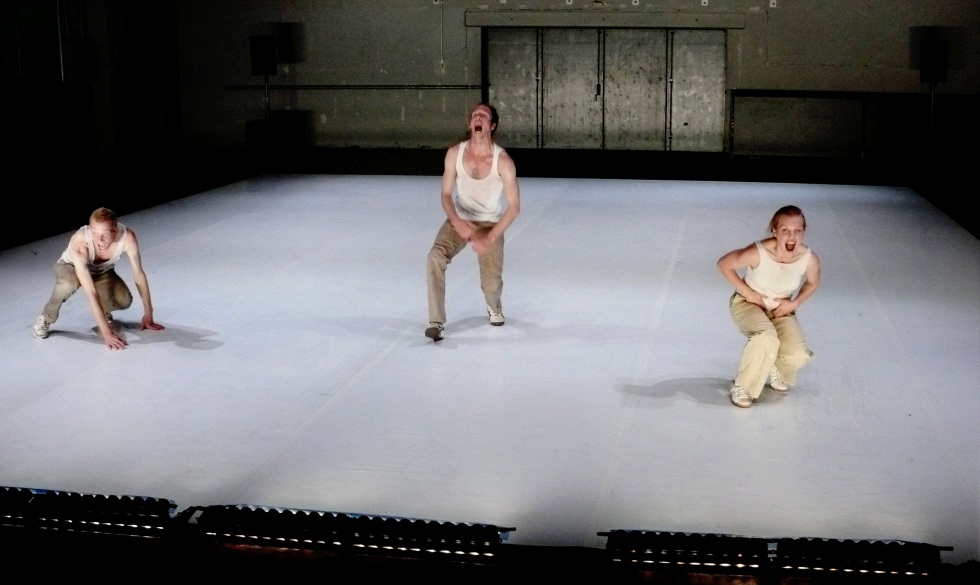

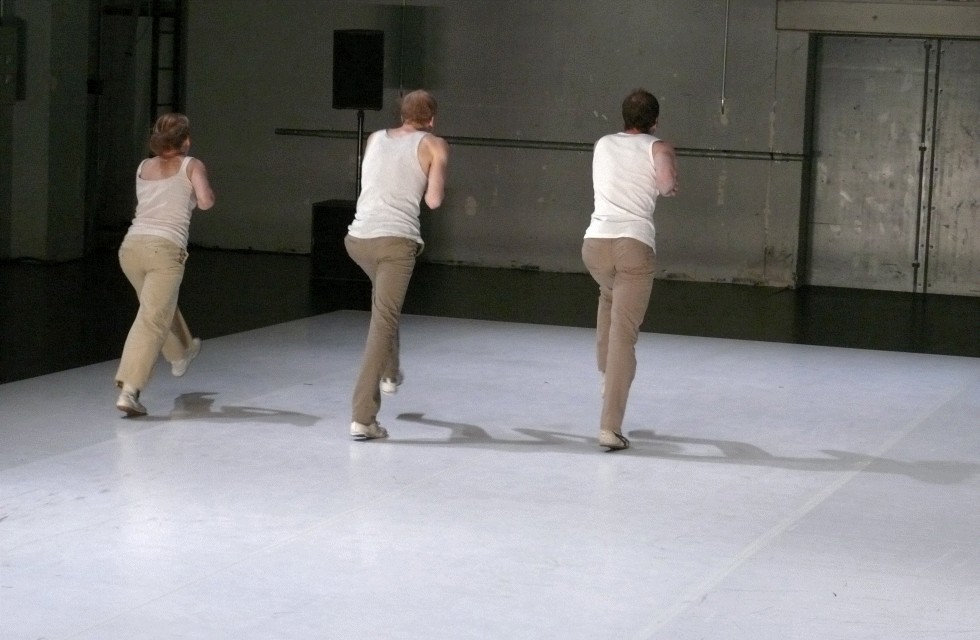

Pounding sound like from a large forging drop hammer fills the room. Three performers in A-shirts and beige pants rise from the floor at the back of the stage and move towards the audience in a slow

motion. The lights from behind project their bodies to the floor as sharp shadows, making their arms appear as claws.

The mouths of the dancers remain widely open during the whole 60-min piece. This gave the figures a dehumanized, fanatic look. Lea Martini said that it took a week of daily exercise to get

used to keep the mouth open all time. Whatever is regarded as normal, she added, might appear so merely because we have exercised it for long enough. The idea deserves a deeper thought.

A model for their movements were old movies and posters of revolutionaries from the communist Russia. Eisenstein's Battleship Potemkin of 1925 was an important source (I wrote about a reconstructed version shown in 2006 at Murnau-Festival in Bielefeld). The performers marched with and without arms and carried out series of arm

movements, all ending up with a throat-cutting gesture. Because fanaticism does not recognize physical limits, the heroes exhausted themselves to death. But even during recurrent collapses they did not give up their exalted expression and kept their mouths open.

Cheering proletariat that they spearheaded was simulated by a recording of crowd shouting out of wild frenzy, played at high volume. The noise of the crowd combined with the stamping industrial sound was intense and obtrusive. A couple of spectators felt so uneasy that they left the room during the performance. The substitution of overwhelming

and unquestionable doctrine for individualism and humanity is a feature that revolutionary heroism and religious fanaticism share. In this way the message of Trip is of burning relevance, though - and this is otherwise tricky to achieve - it avoids political incorrectness.

With "Trip" presented after Cynthia Gonzalez "The Last Breath" on the same day, Roger Merguin, the artistic director of Dampfzentrale responsible for modern dance, aligned two strong choreographies in a tight sequence. I did not consider it a good idea at the beginning as I felt that the spectator needs time for his/her stirred emotions to settle down. On the other hand the impact of the performances is so different that they can be digested - so to speak -

by different parts of the brain.

Since 2008 the city of Bern invests one million Swiss francs to dance annually. As Bern has merely 130,000 inhabitants (metropolitan area 660,000), this is an enviable luxury. Germany spends by far more money on dance per capita than any other country, but cities like Bern and places like Dampfzentrale may still incite our jealousy.

Petr Karlovsky